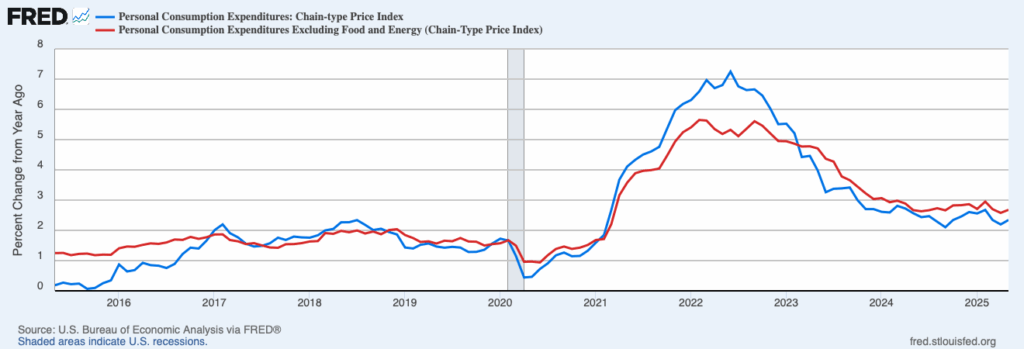

New data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis confirm that inflation remained low in May. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI), which is the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, grew at an annualized rate of 1.6 percent last month. It has averaged 1.1 percent over the last three months and 2.3 percent over the last year.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices but also places more weight on housing services prices, was a bit higher. According to the BEA, core PCEPI grew 2.2 percent in May. It has averaged 1.7 percent over the last three months and 2.7 percent over the last year.

Figure 1. Headline and core PCEPI inflation, May 2015 to May 2025

Inflation is running well below the most recent projections submitted by Fed officials. In June, the median Federal Open Market Committee member projected 3.0 percent PCEPI inflation for 2025, with projections ranging from 2.5 to 3.3 percent. PCEPI inflation has averaged just 2.6 percent year-to-date, which is above the projections submitted by eighteen of nineteen FOMC members.

Figure 2. Distribution of participants’ projections for PCEPI inflation in 2025, as submitted in March and June

In fact, inflation has been running much closer to the projections Fed officials submitted back in March. Three months ago, the median FOMC member projected 2.7 percent inflation for 2025. At that time, projections ranged from 2.5 to 3.4 percent, but the central tendency (i.e., excluding the three highest and three lowest projections) was 2.6 to 2.9 percent. In March, only one member projected inflation would exceed 3.0 percent this year. In June, seven members projected inflation above 3.0 percent.

What changed? Soon after submitting their projections in March, Fed officials learned how high and widespread President Trump’s intended tariff rates would be. Ongoing negotiations, court orders, and Congressional push back now suggest those tariff rates will be lower — and, in some cases, much lower — than those announced in April. Nonetheless, the tariff rates appear to remain higher than Fed officials anticipated they would be back in March.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways the inflation data might evolve in the months ahead. In the first scenario, the pass-through from tariffs will cause prices to rise considerably over the back half of this year. Given year-to-date data, inflation would have to average 3.3 percent over the remainder of 2025 to hit the median FOMC member’s projection. That’s more than double the inflation rate realized in May, and seventy basis points above the average inflation rate realized over the last year. In the second scenario, where passthrough from tariffs is much lower than most Fed officials expect, inflation will continue falling, remain steady, or rise slightly.

In theory, the passthrough from tariffs to the price level should have no effect on monetary policy. The tariffs are a negative supply shock, which the Fed is unable to mitigate. The best the Fed can do (with or without the negative supply shock) is stabilize demand — that is, to keep nominal spending on a stable trajectory.

The most recent projections appear consistent with this look-through-supply-shocks approach. Whereas the median projection for inflation rose considerably from March to June, the implied median projection for nominal spending — which can be constructed by adding the median projections for inflation and real GDP growth — remained unchanged at 4.4 percent.

Monetary policy is more complicated in practice, however. The public might not react to the passthrough from tariffs the way the rational agents in an economic model do. Specifically, the public might mistake the temporary increase in inflation caused by an adverse supply shock as a permanent increase in inflation, and revise their inflation expectations accordingly. Fed officials would then need to meet those higher expectations with faster nominal spending growth, thereby delivering the permanently higher inflation expected; or, leave nominal spending growth unchanged and risk a recession.

At the post-meeting press conference last week, Fed Chair Jerome Powell acknowledged the risk that tariffs will push inflation expectations higher:

The effects on inflation could be short-lived, reflecting a one-time shift in the price level. It’s also possible that the inflationary effects could instead be more persistent. Avoiding that outcome will depend on the size of the tariff effects, on how long it takes for them to pass through fully into prices, and ultimately on keeping longer term inflation expectations well anchored. Our obligation is to keep longer term inflation expectations well anchored and to prevent a one-time increase in the price level from becoming an ongoing inflation problem.

In other words, the Fed might need to keep policy tighter than would be ideal in order to reassure the public that the supply-driven inflation will be temporary.

If monetary policy were close to neutral today, holding the federal funds rate target slightly above neutral in order to keep inflation expectations well-anchored would have little negative effect on near-term economic activity and a neutral to positive effect on longer term economic activity. If monetary policy is already excessively tight, however, the Fed’s hesitancy to cut the federal funds rate target in response to lower-than-expected nominal spending growth could significantly reduce economic activity in the near term, exacerbating the real effects of higher tariffs. Just as the Fed’s hesitancy to raise rates in 2021 and early 2022 allowed inflation to rise, its hesitancy to cut rates in the months ahead would risk causing a recession.