The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Mexico, and Canada harkens back to a not-so-distant past when Congress took its constitutional role “to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations” seriously.

In his final weeks in office, Republican President George H. W. Bush signed the agreement on December 17, 1992. The House and Senate approved NAFTA less than a year later in a bipartisan fashion with Democrat President Bill Clinton signing the Implementation Act in December 1993.

Just over 31 years since, NAFTA and its updated USMCA have proven a boon to the American economy.

The agreement slashed many tariffs immediately upon enactment in 1994. By 2008, nearly all import duties between the three nations had disappeared. Central to the agreement was manufacturing freedom. But NAFTA also removed unfair trade barriers placed on service industries — including banking, insurance, and telecommunications. Guaranteeing fair treatment for foreign investors also spurred cross-border investment. This included protecting their property from expropriation and providing international arbitration in lieu of oft-biased local courts. Patents, copyrights, and trademarks also received protection from piracy and counterfeits to an extent unprecedented in trade deals. Cross-border commerce soon soared. The US, Canada, and Mexico benefited greatly from lower costs, more investment, and streamlined trade.

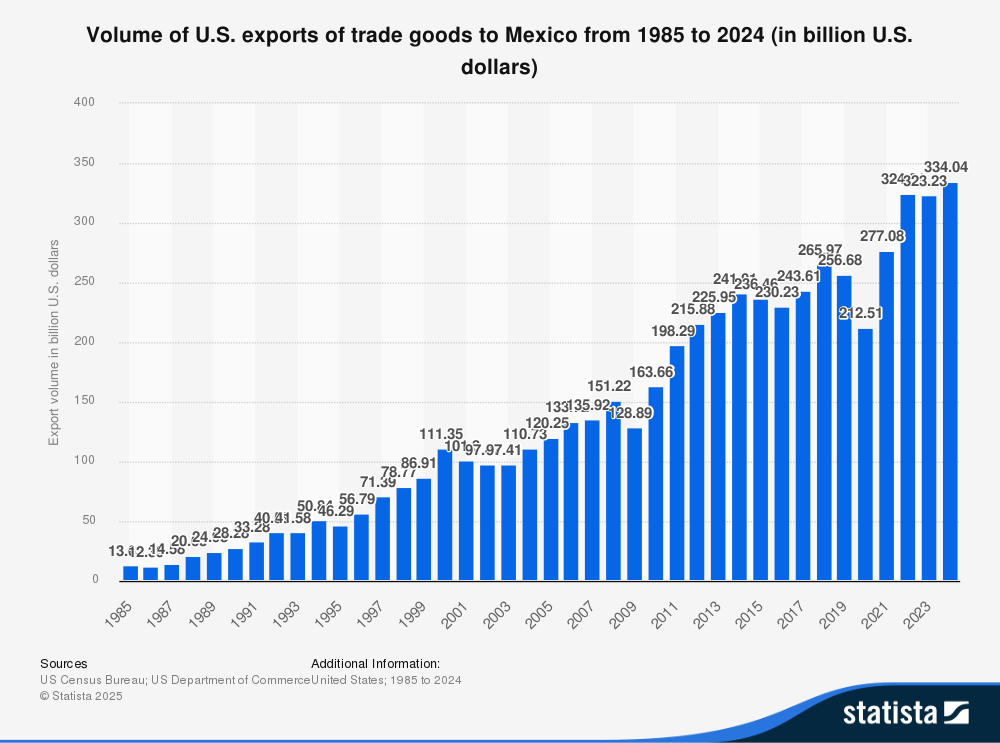

As NAFTA pried open markets by limiting quotas and other non-tariff barriers, trade transformed and blossomed. Since 1994, American exports have nearly tripled, even after you adjust for inflation. American goods exported exceeded $2 trillion last year. Exports from the US to Mexico jumped from about $40 billion a year to an all-time high of $334 billion in 2024. Our exports to Canada more than tripled, rising from $100 billion to a near all-time high of $349 billion last year. Both of America’s NAFTA partners import more than twice as much from the US as China — number three on the list.

No agreement is perfect, of course. Some sectors, notably dairy, received cronyist carveouts. But contrary to popular belief, American exporters enjoyed a manufacturing renaissance.

The US agricultural sector saw a major boost from NAFTA. With tariffs on many farm goods eliminated, exports to Canada and Mexico soared. Corn exports to Mexico jumped from negligible levels to billions of dollars annually, while soybean, pork, and beef shipments also climbed. In 2023, Mexico and Canada accounted for more than 32 percent of US agricultural exports — over $55 billion a year in sales. Farmers in Iowa, Ohio, Nebraska, and Texas literally reap the rewards of this expanded market access.

The auto sector thrived under NAFTA’s integrated supply chains. Tariffs on vehicles and parts dropped to zero, letting companies like Ford, GM, and Chrysler source components from Mexico and Canada at lower costs. This kept US-made cars competitive globally — exports of vehicles to Mexico alone grew from under $1 billion in 1993 to nearly $29 billion in 2024. Plants in Michigan, Ohio, and the Midwest benefited from this cross-border efficiency, even as some assembly shifted south. The American automotive sector exports more than $160 billion annually, nearly doubling in inflation-adjusted terms since 1994. Across the nation, American factories churn out automobiles for export — including BMW’s South Carolina plant which employs 11,000 Americans. Motor vehicles are among the top three exports in 14 states, including Missouri, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee.

Beyond autos, manufacturing broadly gained from cheaper inputs and bigger markets. Machinery, electronics, and chemicals saw export booms — US machinery exports to NAFTA partners tripled in value post-1994. Firms in industrial hubs like Illinois and Pennsylvania found new customers, while lower-cost Mexican imports (like steel or plastic components) trimmed production costs, helping manufacturers stay lean in a global race. America’s aerospace industry now exports nearly $100 billion a year.

The energy sector, particularly oil and gas, benefited as well. Much of the record levels of US-produced oil is sent to Canada for refining before returning to fuel our vehicles. Meanwhile, Canada became the US’s top supplier of some types of crude oil needs. Although the United States produces more oil on net than we consume, petroleum types and uses vary. For this reason, we imported nearly 4 million barrels a day from Canada in 2023 representing 97 percent of their oil exports. Mexico sends refined products north to us as well. The boom in American natural gas production helps supply the energy needs of all three nations — all without tariff taxation. More than half of our natural gas exports flow to Canada and Mexico, 8 percent of our total production. This keeps energy prices stable, directly supports extraction and pipeline jobs in Texas, North Dakota, and elsewhere. Industrial electricity prices — essential to competitive manufacturing — benefit as well.

Retailers and consumer goods companies — like Walmart or food processors — benefit from cheaper imports and a larger export market. American families enjoy Mexican fruits and vegetables — in the middle of winter — at affordable prices. American brands like Coca-Cola, Kraft, and John Deere profit by more sales in Mexico.

Deeper ties with Canada and Mexico drove efficiency, created jobs, and increased output. Of course — some industries like textiles and furniture faced tough competition. It’s a misnomer to claim manufacturing has been “hollowed out.” In fact, the United States is a bigger manufacturing powerhouse today than 30 years ago. Industrial output increased by more than half since 1994 — and is near all-time high today.

At the same time, fewer people are employed in manufacturing despite the increased output because efficiency has surged. Our economy has shifted to much higher-paying, advanced services. In fact, we now export far more of these services than we import. In other words, free trade has allowed us to purchase low-cost products from overseas, focusing on these new high-paying sectors where we enjoy a comparative advantage.

The services sector — including finance, logistics, and tech — expanded under NAFTA. US banks and insurers gained easier access to Canadian and Mexican markets, while cross-border trucking and shipping grew to handle booming physical trade. American service exports to NAFTA partners topped $128 billion in 2023, boosting well-paying white-collar jobs.

Of course, protectionists bemoan the fact that our imports from our partners grew by even more. But a trade deficit is identical to our capital surplus that flows back to the United States often in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI) in businesses here. Since NAFTA’s enactment, FDI exploded more than 500 percent to more than $330 billion annually. This helped spur a doubling in overall worker productivity in the past 40 years. Competition forces producers to innovate. As efficiency grew, GDP across all three nations grew.

It’s not just investors or managers who benefit from rising productivity. Workers share in this abundance of affordable, available, and diverse goods. American families are far better off. Thanks largely to the innovation and efficiencies from free trade, millions of Americans enjoy new opportunities in well-paying professions. Middle-class real annual family income increased more than $28,000 since 1994. By 1980s income standards, middle-class shrank as a share of the population only because millions of these families are now earning what would have been upper middle-class incomes. Yes, that’s in real, inflation-adjusted terms. Meanwhile, a greater percentage of prime-working age adults are employed today than pre-NAFTA.

NAFTA exhibits how widely shared abundance materializes when governments meddle less and let markets work. Trade barriers — tariffs, quotas, and restrictions on investment — distort prices, prop up inefficient producers, and rob consumers of choice.

Tearing down these barriers between the US, Canada, and Mexico generated widespread abundance. Free trade certainly means lower prices for businesses and families. Who wants to pay a Canadian lumber tariff when building a home — or a Mexican tequila tax? But, just as importantly, free trade means the liberty to buy and sell without seeking the approval of or paying off the central planners in Washington, DC.