President John F. Kennedy once said, “We must find ways of returning far more of our dependent people to independence.” President Lyndon B. Johnson sought to meet that challenge by launching the War on Poverty in 1964, insisting that its purpose was not to make people “dependent on the generosity of others,” nor merely to “relieve the symptom of poverty,” but to “cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”

Sixty years and some $20 trillion in welfare spending later, that message appears to have gotten lost. Rather than helping the poor climb out of poverty toward self-reliance, government handouts have instead pulled the ladder away by supplanting work as their primary source of income.

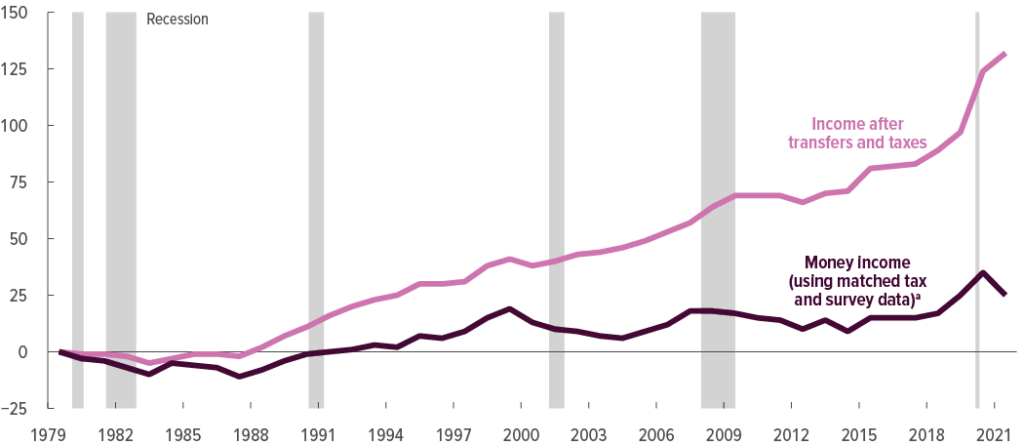

According to January’s Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report, average total income for the poorest households nearly doubled from 1979 to 2022. But most of that increase was fueled by government wealth transfers.

Cumulative Growth of Income Among Households in the Lowest Quintile of the Income Distribution, by Type of Income

Congressional Budget Office, using data from the Census Bureau. In 2021 dollars. Shaded areas show recessions.

If the success of America’s social safety net is measured by how much cash the government can dole out, then it’s a testament to the scale and generosity of the welfare state. But that was never the yardstick the architects of the welfare state themselves used when selling their War on Poverty to the public. Welfare was intended to be a means toward self-sufficiency and independence through work.

Viewed through that lens, the CBO report paints a far more troubling picture: Low-income Americans are receiving an ever-growing share of their financial resources from government transfers instead of work.

In 1979, households in the lowest income quintile earned, on average, about 53 percent of their total income from money income — wages, salaries, business income, and other earnings from private-sector work. Means-tested transfers — government cash and in-kind benefits targeted to low-income households — made up just 26 percent.

Since then, the numbers have gone in completely opposite directions. During the pandemic, income from work plummeted to an all-time low of just 33 percent, while means-tested transfers skyrocketed to 57 percent.

Even after temporary COVID-era benefits expired, about 42 percent of the income of America’s poorest households comes from their own earnings. Government transfers also sit at 42 percent, matching earnings from work dollar-for-dollar.

The means-tested transfer rate — that is, the value of welfare benefits relative to income before government assistance and taxes — tells the same story. In 1979, it stood at 32 percent. By 2022, this figure had more than doubled to 72 percent. In other words, for every dollar a low-income household earned (after counting social insurance like Social Security and Medicare), 72 cents were in welfare benefits. During the pandemic, this reached a staggering 93 percent.

The report’s findings are indicative of a trend that is all too common in America’s “social safety net.” Rather than enabling the poor to rely on their own earnings, welfare traps people in government dependency.

Real federal welfare spending has soared 765 percent, and now, despite unprecedented economic gains for low-income Americans, more of them are dependent on government assistance than at any point in the country’s history. That’s hardly an outcome taxpayers should be proud of in a country that styles itself as the land of opportunity. Indeed, if welfare’s purpose is to provide transitional support, then persistently high caseloads should signal that government assistance has become a destination, not a bridge.

CBO via USGovernmentSpending.com. Chart by FederalSafetyNet.com

If the federal government is going to be in the business of wealth redistribution at all, taxpayers are entitled to demand that it cultivate a culture of work, as then-senator Joe Biden said before the 1996 welfare reforms. But if taxpayers have been pouring trillions of dollars into a money pit that has failed to achieve its own stated goals for over 60 years, it’s time for a serious reckoning.

It is neither efficient nor compassionate for the government to create a perpetual underclass of citizens trapped in a cycle of dependency at the taxpayers’ expense. No amount of political or moral grandstanding can ever justify this state of affairs.

As Congress floats the idea of a second reconciliation bill going into 2026 amid the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA)’s historic welfare reforms, it would do well to remember that a paying job will always be the best anti-poverty program.

The CBO’s report should be a warning. If the goal is independence, welfare policy must be judged by whether it increases work and reduces reliance on government aid. But if the welfare state has become the narcotic President Franklin ‘New Deal’ Roosevelt himself warned against, then Congress should follow his prescription: “The federal government must and shall quit this business of relief.”