Towards the end of last year, Pope Leo XIV released his first Apostolic Exhortation, titled Dilexi Te (Latin for “I have loved you”). Many of the major themes of this exhortation closely carried over from the themes developed by Francis in his papacy.

Included in this is a specific ethical focus on economic actions and economic systems. The exhortation spans nearly 20,000 words, covers significant ground, and maintains a central focus on God’s love for the poor. The pope argues that the dignity of the poor is central both in scripture and in the history of the Roman Catholic Church.

I agree with much of what Leo has to say throughout the exhortation, so I will focus most of my comments on the area where I would differ most sharply from him — on the economic system.

Paragraph 92 in particular addresses economic policy. Leo says:

We must continue, then, to denounce the “dictatorship of an economy that kills,” and to recognize that “while the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially, so too is the gap separating the majority from the prosperity enjoyed by those happy few. This imbalance is the result of ideologies that defend the absolute autonomy of the marketplace and financial speculation. Consequently, they reject the right of states, charged with vigilance for the common good, to exercise any form of control. A new tyranny is being born, invisible and often virtual, which unilaterally and relentlessly imposes its own laws and rules.” There is no shortage of theories attempting to justify the present state of affairs or to explain that economic thinking requires us to wait for invisible market forces to resolve everything. Nevertheless, the dignity of every human person must be respected today, not tomorrow, and the extreme poverty of all those to whom this dignity is denied should constantly weigh upon our consciences.

When reading this, I felt mostly surprised by the characterization of our current situation. A significant chunk of this involves a quote from Pope Francis’ Evangelii Gaudium, wherein he claims inequality has bred ideologies that defend absolute autonomy of the marketplace against state regulation.

The difficulty I find here is that, insofar as these ideologies have been bred (which I’m unsure of), they appear not to have been very successful. Regulation and regulatory agencies continue to outpace market freedom in the West. While measuring this isn’t easy, we have some indications. The Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Report shows the current economic freedom score of the US is 8.1 out of 10. This is the fifth-lowest score since The Fraser Institute started keeping annual data in 2000.

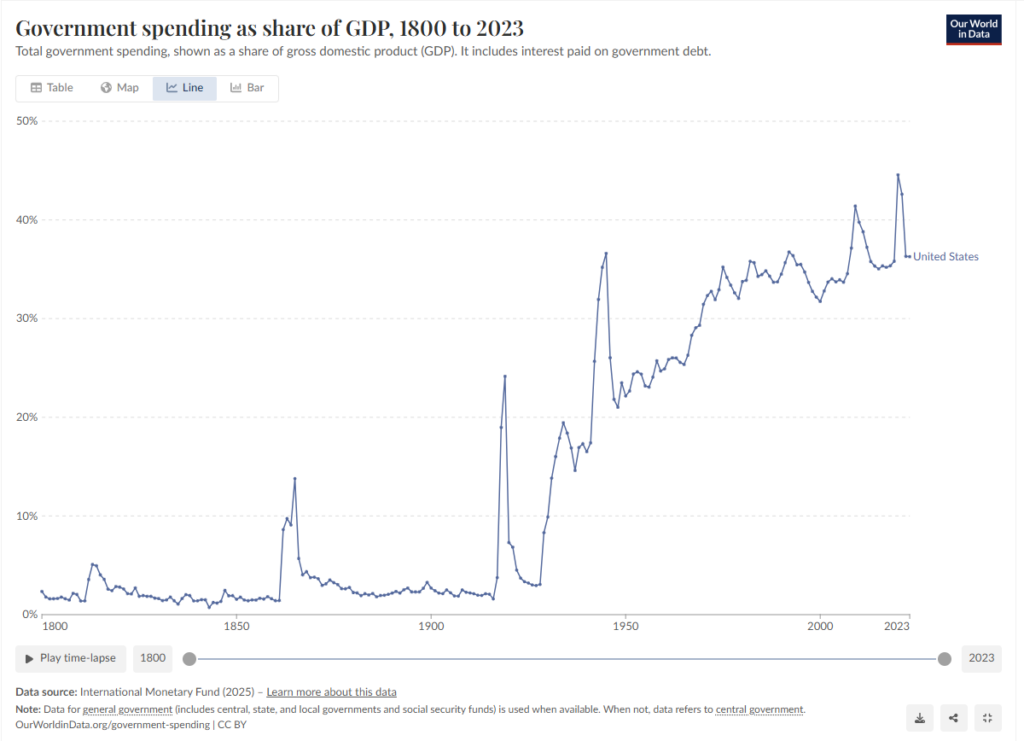

Another indicator is that government spending is 36.3 percent of GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. Excluding outlier events like World War II and the Great Depression, this is a higher level than nearly any time in American history. How could we say the government’s “right” to exercise control over markets is too limited at a time when it commands a larger share of resources than at any time in the country’s history?

The pope isn’t writing only about America, but many of the notable trends in America are also unfolding elsewhere. Europe’s regulatory ramp-up has been even more pronounced with the exhaustive bureaucratic standards that permeate the EU.

What about outside the West? Well, over the decades, economic freedom has tended to increase throughout the developing world, and importantly, increasing economic freedom has corresponded with a rise in the standard of living. Economically free countries tend to be richer and healthier than economically unfree countries.

Does the Invisible Hand Fix Everything?

The exhortation seems to anticipate this kind of response, saying, “there is no shortage of theories attempting to justify the present state of affairs or to explain that economic thinking requires us to wait for invisible market forces to resolve everything.”

My difficulty with this statement is that I’m unsure of anybody who argues that we are required to wait for invisible market forces to resolve everything. Champions of free markets tend to be very open about the fact that some problems are not solved by the market, and defer to the importance of individual responsibility, private charity, and formal and informal institutions to handle some problems.

This section seems to rebuff the belief that “the invisible hand” is the only way for things to get better. But this has never been claimed by anyone. Rather, supporters of markets argue that the invisible hand is a solution to some significant problems, and we inhibit this force at the peril of the poor. Claiming descriptively that the market is important for helping people escape poverty is far from identical to claiming that no one should be allowed to help anyone in any other manner.

We could imagine a society where the cultural bias is to believe only impersonal market forces should solve problems, but I think it would be mistaken to believe that our society has that bias. Rather if we have a bias, it is that any time there is a problem, it demands a top-down, political solution.

On a similar note, the pope argues, “At times, pseudo-scientific data are invoked to support the claim that a free market economy will automatically solve the problem of poverty.” I’m not sure what data he’s referring to, but I think it’s reasonable to argue that, at times, some economists, focused on the mere models of economics, have put the “automatic equilibrium adjustment” of the market in the foreground.

Many defenders of economics have, however, labored to demonstrate that the process is not automatic, but rather, is the result of individuals endowed with creativity, opportunity, and grit attempting to add value in previously unforeseen ways. On this, consider FA Hayek’s piece The Meaning of Competition.

Perhaps the “automatic” aspect bothers some people, as economists assert that markets can improve the lot of the poor regardless of the intention of the market participants. While we would certainly prefer people to want to improve the lot of the poor, I see it as a Common Grace that there could be a system that does not depend on that intentionally.

Importantly, markets do not require good intentions, but do not prevent them, and, I’d argue, the humanizing aspects of markets even encourage good intentions.

The Dignity of the Least of These

Pope Leo continues by arguing that the current economic system emphasizes self-reliance and success, and asks based on this:

Does this mean that the less gifted are not human beings? Or that the weak do not have the same dignity as ourselves? Are those born with fewer opportunities of lesser value as human beings? Should they limit themselves merely to surviving?

In this, I have no problem agreeing with the pope. I don’t believe a person’s dignity is contingent on their ability. If we accept this, though, the necessary next step is to ask how do we best ensure the dignity of the poor? A state, even one charged with the upholding of the common good, may be constrained by incomplete knowledge or perverse incentives such that its intervention will only harm the dignity of the poor more.

While it is unwise to outsource responsibilities to impersonal invisible forces and hope improvement trickles down, the same is true of relying on impersonal central forces.

To Leo’s credit, he seems to recognize this issue as well, though it seems to be more in the background. He argues, citing Francis, that welfare projects are, at best, provisional responses until deeper structural issues are resolved. He also acknowledges that solutions do not necessarily come from above:

One structural issue that cannot realistically be resolved from above and needs to be addressed as quickly as possible has to do with the locations, neighborhoods, homes and cities where the poor live and spend their time.

He echoes this sentiment later and critiques those who say, “ it is the government’s job to care for them, or that it would be better not to lift them out of their poverty but simply to teach them to work.”

Here, I think we find the key to Leo’s argument and my central area of agreement. Pope Leo argues that our responsibility to care for the poor cannot be simply outsourced to some external process (whether government, market, spiritual or otherwise).

While I tend to think the exhortation overstates the zeal of defenders of free markets and the extent to which we live in a world dominated by markets (rather than regulation), the message that moral responsibility for the poor cannot be outsourced to “someone else” is a valuable one.