A cursory review of public sentiment portrays the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as a triumph of social policy, with nearly two-thirds of Americans holding a favorable view of the 2010 healthcare law. This popularity rests on a precarious foundation, as the ACA’s sustainability is undermined by fragile structural and financial mechanisms. Just like Medicare, beneath its widespread acclaim lies a contentious and unsustainable undercurrent.

ACA and Medicare, by design, impose a disproportionate burden on younger generations.

The ACA’s risk-pooling mechanisms and individual mandate require younger, healthier individuals to subsidize older, high-risk populations, inflating premiums for those with limited financial resources. Medicare’s payroll tax structure intensifies this inequity, extracting funds from young workers to sustain a program facing looming insolvency risks. According to the Medicare Trustees’ 2024 Report, the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund is projected to be depleted by 2036.

This intergenerational transfer prioritizes immediate social benefits over long-term fiscal sustainability, potentially jeopardizing future benefits for younger cohorts. Such dynamics raise critical questions about distributive justice, challenging the fairness of policies that burden the young to support current beneficiaries while offering uncertain returns.

The Flawed Formation

Pragmatic politics necessitates negotiation and maneuvering among competing interests, and the adoption of the ACA was no exception. Lobbying groups representing healthcare interests spent $263 million in the first half of 2009 to shape the legislation, according to OpenSecrets.

Older generations wielded significant political influence during this process. Older, sicker patients consume more healthcare, while younger, healthier individuals are essential for insurers to balance risk pools — paying premiums without incurring substantial medical costs.

The Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker reports that in 2021, individuals aged 55 and over accounted for 56 percent of total health spending, despite comprising only 31 percent of the population, while those under 35 represented 44 percent of the population but only 21 percent of spending. Per capita, older adults (65+) spent $11,300 annually, compared to $2,000 for ages 5–17 and $4,500 for ages 18–34, per Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data.

This disparity was a focal point during the ACA’s formation, and younger generations bore the brunt of the outcome. Insurance lobbyists advocated for a 5:1 premium ratio between older (high-usage) and younger (low-usage) clients, reflecting actuarial costs. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) pushed for a 2:1 ratio to protect older enrollees, and the final compromise, set at 3:1 under Section 1201 of the ACA, capped older enrollees’ premiums at three times those of younger ones.

The younger generation lost the political battle.

The established ratio deviates from fairness. A 2016 American Academy of Actuaries study notes that the 3:1 age band compresses pricing, forcing younger enrollees to pay premiums exceeding their expected healthcare utilization. For example, a healthy 25-year-old with minimal medical needs might pay a premium far outsizing their spend. This effectively subsidizes the insurance coverage of a 60-year-old with multiple comorbidities.

The ACA’s Medicaid Mirage: A Numbers Game with Hidden Costs

The ACA is often praised for reducing the uninsured rate, with 20-24 million gaining coverage from 2010 to 2016. But a portion of this achievement stems from Medicaid expansion, raising questions about the quality and sustainability of the care provided. A reliance on Medicaid distorts the ACA’s success, burdens the system and patients with subpar care, and shifts costs onto younger taxpayers, challenging its equitable promise.

The KFF noted 91 million total Medicaid enrollees in 2022, up from 57 million in 2010. Medicaid expanded enrollment by 21.3 million people in 2024. One in five people now use Medicaid as their primary program for health insurance. This is expensive, and Medicaid — funded mostly by federal and state taxes from working-age Americans — is putting a growing strain on state budgets.

California, for example, is estimated to spend $42 billion on Medi-Cal (Medicaid) in 2025-2026. This is a $4.5 billion increase over the previous budget. The state just had to take out a $3.44 billion loan to cover Medicaid expenses for a month.

This is not financially sustainable.

This Medicaid approach is doubly problematic for patients due to the program’s structural deficiencies in delivering access to quality care. Medicaid’s low reimbursement rates — averaging 70 percent of Medicare’s, per CMS — deter provider participation. Medicaid patients have a 1.6-fold lower likelihood in successfully scheduling a primary care appointment and a 3.3-fold lower likelihood in successfully scheduling a specialty appointment when compared with private insurance.

Critics might argue that Medicaid expansion addresses unmet needs, and there is merit to some of those claims. But these gains are overshadowed by access barriers and fiscal unsustainability. Significant opportunity costs are left unmet.

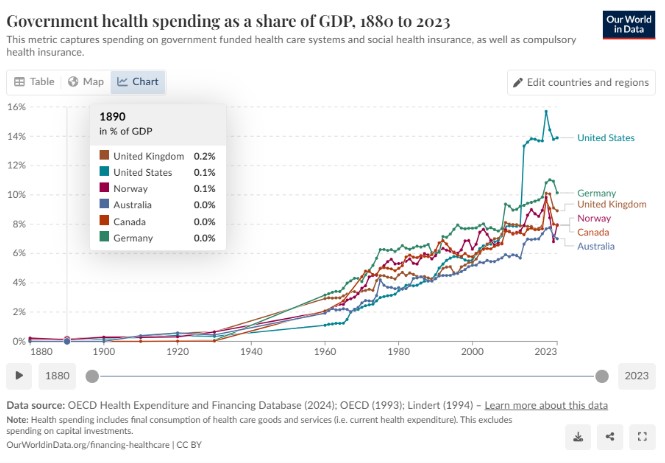

Image Credit: Our World in Data

Intergenerational Inequity: The Fragile Fiscal Future of the ACA and Medicare

The notion of a social contract suggests that generational taxation burdens balance over time, but a critical question persists: will promised benefits endure for future generations? This concern impacts both the ACA and Medicare, both of which impose significant costs on younger cohorts while ignoring solvency and long-term viability risks.

Medicare beneficiaries often receive benefits far exceeding their contributions, creating a fiscal imbalance. The Urban Institute estimates that a 2025 retiree, contributing $87,000 in payroll taxes over their career will receive $274,000 in Medicare benefits (inflation-adjusted). Low-income beneficiaries, contributing minimal taxes, benefit significantly. An aging population, sluggish birth rate, and rising costs may force benefit cuts or tax hikes, and possible diminishing returns for future contributors.

The ACA’s fiscal framework similarly relies on subsidies and taxes under pressure. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts $1 trillion in marketplace subsidies over the next decade, driven by rising premiums and enrollment. The ACA has been able to shield the true cost of insurance by offering premium tax credits. These tax credits create artificial demand and support for the ACA by cloaking the true cost of insurance. These tax credits are available to incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level.

Without tax subsidies, the average family of four would pay $27,025 for health insurance in 2024. If these expire in 2025, as they are set to do, the CBO projects 2.2 million will lose coverage in 2026. Premiums would increase 4.3 percent in 2026, and an estimated 7.9 percent in 2027. To put this in context, for those earning 400 percent of the poverty level, premiums could increase by approximately $2,900 per person each year.The ACA and Medicare’s insolvency risks undermine their equitable vision.

Younger generations, taxed heavily today, may inherit a hollowed-out system unable to deliver care. Without reforms, this trajectory betrays the cohort sustaining it, raising profound concerns about distributive justice. The ACA’s ambition was not its downfall; its disregard for economic principles will be. Subsidies without supply-side reforms (e.g., increasing physicians or lowering drug costs) inflate demand against constrained resources. Mandates without flexibility stifle markets. Moral hazard without cost containment will break the system that’s profiting insurance companies over physicians and patients.