Winning a case against the federal government is difficult. Most federal agencies are well represented by an army of skilled attorneys. The Department of Justice via the Office of the Solicitor General represents the federal government before the US Supreme Court, winning most of its cases each year.

What’s less clear is why these agencies enjoy an even greater rate of success within their own court systems. Most people are unaware of America’s submerged judiciary known as administrative law courts (ALCs) and their estimated 3,000+ administrative law judges (ALJs).

These are in-house quasi-judicial tribunals within approximately 40 federal agencies that adjudicate legal disputes involving regulations and public benefits. ALCs allow agencies to resolve many of their problems in-house without needing to go before an impartial federal court. While Congress intended for ALCs to be statutorily and functionally independent from the agencies they adjudicate for, many agencies circumvent this separation.

Below, I offer a quick glimpse into my ongoing research on the home court advantage in agency adjudication, weighing an agency’s rate of success before its own ALC vs. its success before the Supreme Court.

Administrative Law Courts are Unfair

Federal ALCs stack the deck against private litigants in adjudication, primarily by adhering to the agency’s internal set of legal procedures.

This includes reversing the burden of proof, denying access to a jury trial, and delaying public hearings. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was even caught secretly sharing information between its ALJs and prosecutorial staff. Rather than provide new hearings or outsource these cases to federal court, the SEC dismissed them as a “controlled deficiency.”

Some ALCs, like in the National Labor Relations Board, enable the Board’s clerk to revise draft ALJ opinions if directed to do so. This enables the Board to manipulate case decisions before they receive administrative appeals, while undermining their ALJs’ decisional independence under the law.

Other agencies, like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), have reduced their ALJs’ powers to exert greater control over case outcomes. This came after a rare set of losses for the agency in the Illumina Grail and Juul Labs antitrust rulings. The FTC had typically won 100 percent of its adjudicated cases. It took steps to avoid being foiled again.

Breaking New Ground

Until now, no one has attempted to uncover the true extent of agency advantages in adjudication and in-house success rates. My research seeks to uncover if institutional factors contribute to an agency’s high rate of success before its ALC.

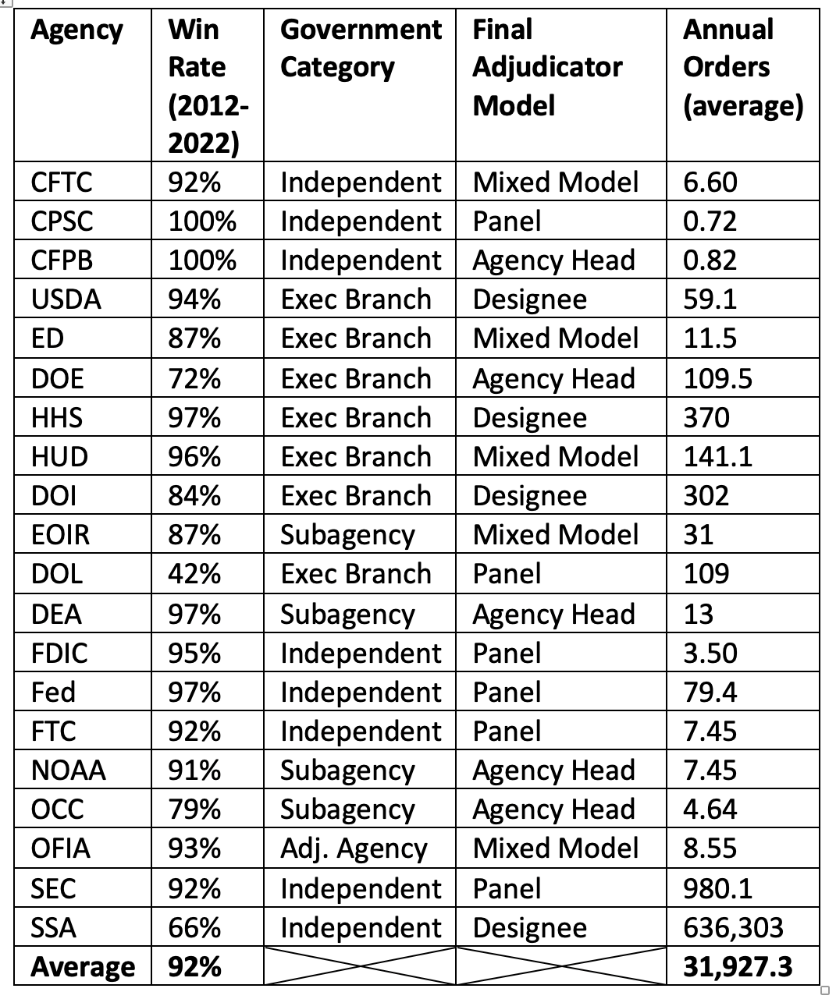

I researched every adversary adjudicatory decision by an ALC from 2012-2022. My preliminary results cover annual ALJ orders from 20 of the 42 known federal ALCs (mean = 31,927), much of which is attributed to the Social Security Administration’s annual benefits cases.

My early findings suggest that agencies win 92 percent of their cases against a private party in-house (Table 1). By comparison, the federal government won only 55 percent of its cases before the Supreme Court during the same period (Table 2). The scales are clearly tipped in cases heard by ALCs.

Table 1: ALC data by agency

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 (11-year avg) 39% 57% 61% 62% 35% 58% 39% 55% 74% 63% 58% 55% Table 2: Fed Gov Win Rate (SCOTUS) Annual, and 11-year average

My research explores certain institutional factors that may contribute to an agency’s heightened rate of success before its ALC. So far, this includes independent variables representing: the number of ALJs at each agency, the agency’s annual number of adjudicatory orders, and the size of the agency’s legal staff. I also control for the government category (subagency, independent, etc.) and the agency’s final adjudicator model (specifying the agency official/s adjudicating appeals).

I ran a multiple linear regression to test the effect of each variable on the agency’s rate of success before its ALC. The results of my regression point to a statistically significant model as at the <.001 level. No single variable proved to be statistically significant from this early test. Nonetheless, by incorporating the remaining 22 agencies and additional variables, we may uncover a factor that predicts agency success.

Table 3: Regression Results. Generated in SPSS

Table 4: Model Summary. Generated in SPSS

What does this mean for the average American?

The preliminary results of my analysis suggest that there are likely multiple institutional factors that contribute to an agency’s heightened success before its ALC. With this in mind, Americans should be deeply worried about agency adjudication.

Many ALCs impose cost-barriers that only wealthy litigants can scale. There are often compounding costs for litigants stuck in protracted adjudication. This burden is exacerbated for those appealing their cases to federal courts. In the face of such high costs and unlikely odds for success, most people are forced to back down and settle with the agency.

Some litigants have seized rare victories against ALCs in federal court. Last year, the Supreme Court’s decision in SEC v. Jarkesy liberated George Jarkesy from a $300K monetary penalty and nearly 14-year legal ordeal within the SEC’s tribunal. Similarly, Michelle Cochran struggled for seven years against the SEC’s court before receiving proper justice in the Supreme Court’s Axon v. FTC (2023) ruling.

From the above research, we learn that agencies win 92 percent of their cases before ALJs compared to 55 percent when represented before Supreme Court Justices. This suggests that an agency’s in-house advantage far exceeds the federal government’s ability to win before an impartial court.

This early research points to an alarming area of bureaucratic dominance. We deserve to know more about these shadowy ALCs and what factors contribute to an agency’s ability to win virtually all its cases in-house. This research suggests that the scales of justice need serious rebalancing.

More about Administrative Law Court Reform