Upon taking office in January, President Donald Trump should fire Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. Trump should do so not because he has any policy dispute with the chairman, but to make clear that the Constitution makes all executive branch officials responsible to the president.

Indeed, to preserve the constitutional legitimacy of the Federal Reserve, Powell and his fellow members of the board of governors should resign. Then, to quiet the inevitable critics, Trump should appoint an outstanding academic economist or experienced banker to continue the campaign against inflation.

Trump and Powell have long been on a collision course. Trump has already signaled that he might want to fire the Fed chair. In a 2020 news conference, he stated bluntly, ‘I have the right to remove’ him. For his part, Powell has been equally categorical. Asked at a recent news conference whether Trump could fire him, Powell said that that was ‘not permitted under the law.’

Powell says Trump couldn’t fire him even if he tried. If Trump were to remove the Fed chair, perhaps the most politically insulated official in the federal bureaucracy, he would display his seriousness in uprooting an unelected bureaucracy that, in the name of public health and safety, has stifled the economy and seized political power.

We will not challenge the prevailing wisdom that control of the money supply is best kept out of the hands of elected politicians. Politicians have a short-term interest in lowering interest rates to spur economic growth, even though they might spark inflation that will inflict more severe long-term harm.

But on similar reasoning, the benefits of policymaking by insulated experts could extend to all the federal bureaucracies – why should bankers remain independent, when generals in charge of the nuclear arsenal are not? For better or worse, however, the Constitution commits to the president the final say in such decisions.

Even though Trump himself appointed Powell as Fed chair in 2017, their quarrel has simmered for years. It arises out of the Fed’s power over national monetary policy, which includes the effective authority to set interest rates. Although the Fed cannot completely dictate rates, especially for long-term borrowing, it does set short-term rates through its buying and selling of government securities and its lending facilities.

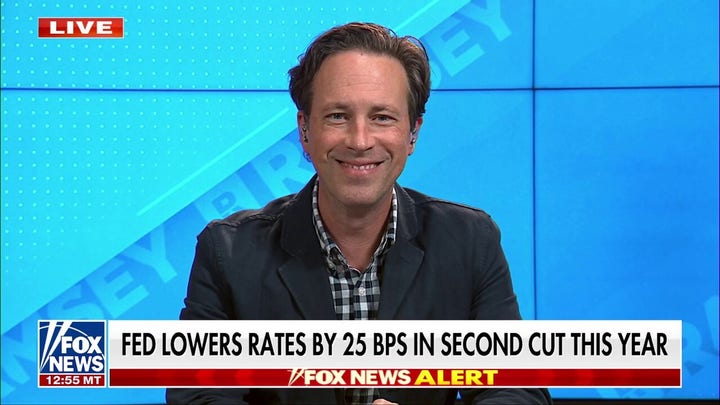

The Fed’s decisions impact inflation, employment and economic growth, and even determine how much interest the government itself must pay on the national debt. And because the amount of the national debt now is so extraordinarily high – the cost of servicing it, now at $882 billion annually, exceeds national defense spending – an incoming president might well be expected to lean on the Fed to help keep the government’s debt servicing costs down. The Fed is already bringing down short-term interest rates after a period of raising Treasury bill rates sharply, from almost zero in early 2022 to 5.34% in late 2023, to squelch Biden-era inflation.